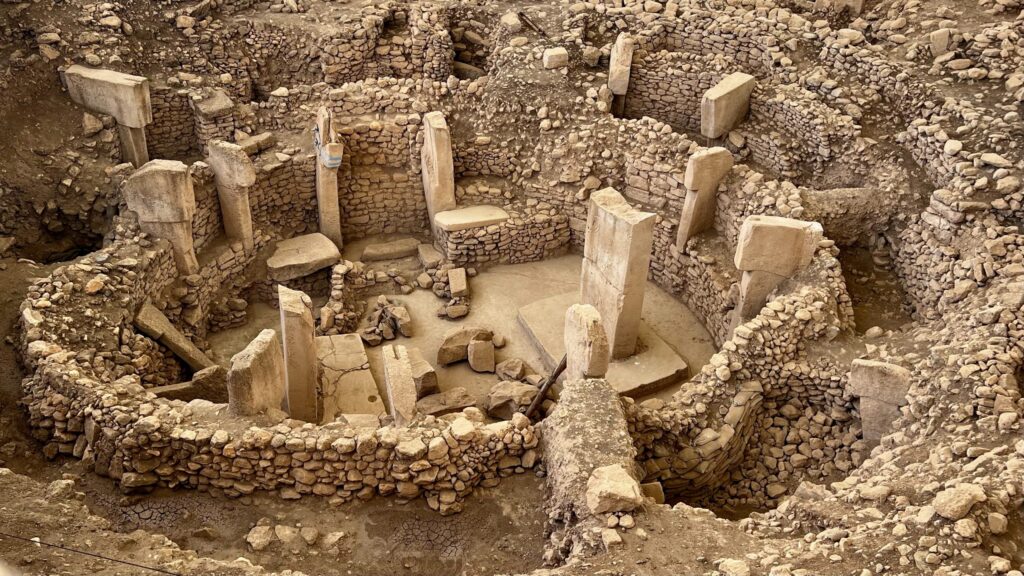

Human civilization’s fascination with stone is as old as the dawn of organized society itself. The oldest surviving monuments—those enigmatic megalithic structures—mark the landscapes of continents, standing as silent witnesses to the earliest chapters of human social and spiritual evolution. These structures, composed of massive stones assembled by prehistoric peoples, not only showcase the technological prowess of our ancestors but also offer profound insight into their beliefs, rituals, and ways of life. From the monumental circles of Göbekli Tepe in Turkey to the cosmic alignments of Nabta Playa in Africa, ancient megaliths unite human cultures across time and geography in a monumental testament to our shared heritage.

Understanding Megalithic Structures

The term megalith derives from the Greek words mega (large) and lithos (stone). Megalithic structures are architectural monuments formed from large, unworked or roughly shaped stones, generally dating back to the Neolithic (New Stone Age) and early Bronze Age. Their construction predates the wheel, written language, and many organized societies. These structures come in several types—standing stones (menhirs), dolmens (chamber tombs), stone circles (henge monuments), passage graves, and more—all assembled painstakingly without modern machinery.

Unlike later stone buildings, megalithic monuments rarely utilized mortar or intricate carving in their earliest phases. Instead, their enduring presence testifies to the sheer ingenuity and brute effort of ancient communities. The motives for their construction were equally monumental, spanning religious observance, burial, territorial marking, social unity, and astronomical calculation.

Göbekli Tepe: The World’s Oldest Temple Complex

Preeminent among the world’s megalithic marvels is Göbekli Tepe in southeastern Turkey. Archaeologists widely consider Göbekli Tepe the world’s oldest known temple complex, dating back to at least 9500 BCE—millennia before Stonehenge or the Pyramids. Here, massive T-shaped limestone pillars, some standing over 16 feet tall and weighing up to 20 tons, rise in circular precincts. Many are richly engraved with bas-reliefs of animals, abstract symbols, and stylized humans, suggesting deep symbolic meaning.

Göbekli Tepe’s builders were likely hunter-gatherers, not settled agriculturalists. This disrupts the conventional narrative of civilization’s rise: it was once assumed that monumental architecture only appeared after people began farming and settled into urban societies. Instead, Göbekli Tepe’s story reveals that even small, mobile communities could organize the collective labor and engineering know-how to create imposing and intricate religious centers.

The function of the site remains debated. Some researchers interpret it as a ceremonial or ritual site, possibly for communal gatherings or ancestor worship. Others suggest it had astronomical alignments or functioned as a cathedral on a hill where various groups might converge, reinforcing social identities through shared ritual practice. The purposeful burial of several enclosures over time—filled with stone tools, animal and human bones, and debris—attests to complex and evolving rituals. Its sheer scale and large number of decorated pillars suggest the site was of immense cultural significance.

Nabta Playa: Early Astronomy in Stone

Across the Saharan sands of Egypt, nearly 700 miles south of Giza, lies the enigmatic stone circle of Nabta Playa. Dated to approximately 7000 years ago, Nabta Playa may be the world’s earliest astronomical observatory. Built by a community of semi-nomadic cattle herders, the stone alignments are believed to have charted the summer solstice, helping predict the arrival of monsoon rains and thus survival-critical water supplies.

Arranged in circular configurations and rows, these stones appear to mark not only astronomical events but may also have delimited ritual or ceremonial spaces. Despite harsh desert conditions today, the area was once a seasonal lake, drawing people together for ceremonies and perhaps collective feasting. The symbolic and practical integration of astronomical observation—central to both ritual and subsistence—demonstrates early humans’ sophisticated grasp of the sky’s regularities.

Debate persists regarding the primary function of Nabta Playa’s stones: were they primarily ceremonial, funerary, astronomical, or social in function? Most scholars conclude that these roles were inseparable, echoing how megalithic sites worldwide tie together practical needs, communal identity, and spiritual meaning.

Megaliths Across Time and Place: The Global Phenomenon

While Göbekli Tepe and Nabta Playa are sterling examples of early megalithic construction, the phenomenon is global. Throughout Europe, the Middle East, Africa, and even Oceania, ancient people erected enormous stones with astonishing similarity, despite great separation in time, culture, and circumstance.

Europe:

Europe is dotted with megalithic wonders. France’s Brittany region boasts the Carnac stones, hundreds of parallel rows of standing stones whose arrangement remains a mystery. In Britain, the megalithic tradition is epitomized by Stonehenge—a massive stone circle constructed over generations, with astronomical alignments and a possible function as a procession route, healing site, cemetery, and more. Ireland’s passage graves, such as Newgrange, combine sophisticated engineering with solar alignments, as seen in the famous illumination of its burial chamber at winter solstice.

Malta:

On the Mediterranean islands of Malta, the world’s oldest free-standing stone structures stand: the Megalithic Temples of Malta. Built between 3600 and 2500 BCE, temples like Ġgantija and Ħaġar Qim are constructed from gigantic limestone blocks, some weighing over 20 tons. Intricate carvings, altars, and oracular chambers suggest use for ritual feasting and goddess worship.

Asia and Beyond:

Megalithic monuments are found in India (notably in the states of Karnataka and Meghalaya), Korea (where dolmens mark ancient grave sites), and Java (Gunung Padang, a stepped pyramid composed of basalt columns). Polynesia’s Easter Island is world-famous for its 900 enigmatic Moai statues—massive stone figures built by the Rapa Nui people—though these are more recent, originating around the 13th century CE.

Construction Techniques and Social Implications

How did prehistoric builders move and set stones weighing several tons, often across considerable distances and challenging terrain? Research suggests some fundamental techniques: dragging on wooden sledges, rolling on wooden logs, levering, and constructing earthen ramps. Ques of stones’ sources often reveal impressive logistics, as many monuments’ rocks came from quarries miles away.

The existence of megaliths proves ancient societies could plan elaborate projects, work cooperatively over years or generations, and invest immense resources in symbolic architecture. These projects likely required powerful leaders, skilled engineers, and a stable enough environment to support communal labor.

Ritual and Belief: The Spiritual Power of Stone

At the heart of megalithic monumentalism lies a reverence for stone—a substance imbued with permanence, stability, and power. Many megalithic sites functioned as sacred landscapes where the living mediated relationships with the ancestors, cosmic order, and the cycles of fertility and death. The alignment of certain monuments with solar, lunar, or stellar events (as at Newgrange or Nabta Playa) ties communal identity and religious practice to the rhythms of nature and the heavens.

Burial and ancestor cult were widespread motifs: dolmens and passage graves served as repositories for the dead, with architectural elements severely restricting access, heightening mystery and sacredness. Feasting, sacrifice, and the marking of life’s rites of passage unfolded amidst these stones—connecting individual and collective to something vast and eternal.

Evolving Theories and Enduring Mysteries

Despite centuries of research, many questions remain about ancient megalithic structures. Why did disparate societies across the planet independently develop a stone-building tradition? What precise beliefs animated their labor? Was knowledge transferred, or did the impulse for monumentality arise independently in response to similar social or ecological triggers?

Some fringe theories invoke lost civilizations or even alien influence, but mainstream scholarship attributes the emergence of megalithic monuments to a convergence of social, technological, and cosmological factors. What unites these sites, even amid variance, is their role in binding society, marking sacred space, and anchoring the human world within the broader cosmos.

Modern Significance: Cultural Heritage and Lessons Learned

Today, megalithic monuments serve as both national treasures and UNESCO World Heritage Sites, attracting researchers, spiritual seekers, and tourists alike. Ongoing excavations at Göbekli Tepe, advances in archaeoastronomy, and the utilization of non-invasive survey technologies promise new surprises from old stones.

Yet, ancient megalithic structures also remind us of the creative capacities of societies once labeled primitive. They challenge us to recognize cultural complexity and artistic achievement wherever it is found. In honoring these enduring monuments, humanity finds connection with ancestors—bound by stone, spirit, and the eternal quest to leave a mark on the world.